The Paradox of Enforcing and Empathy: Holding the Line While Understanding Another’s Perspective

July 18, 2025

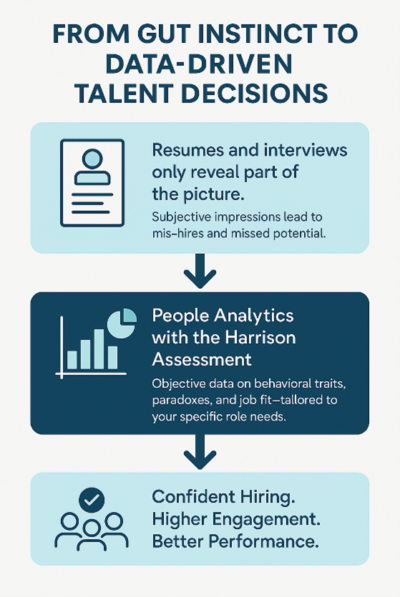

Hiring isn’t just about resumes—it’s about data-driven insight.

August 12, 2025As a manager, do you find yourself doing your team’s work—just to be helpful?

Do you say “yes” to work so often that it creates stress for you?

Do you help others so much that you don’t have time to do your own job?

If so, you’ve got a monkey on your back.

What’s the Monkey?

A “monkey” is a task or problem that belongs to someone else—but somehow ends up on your plate.

I first learned about this idea years ago, when I was a young CEO of a natural gas trading company. A board member asked if I had ever read “the monkey article.” I hadn’t—so he handed me a copy on the spot.

The article was “Who’s Got the Monkey?” by William Oncken, Jr. and Donald L. Wass—still one of Harvard Business Review’s most popular pieces. And when I read it, I realized I was guilty of a common leadership mistake: I was taking on work that wasn’t mine.

What It Looks Like in Action

Here’s a classic monkey moment, straight from the article:

You’re walking down the hall. One of your direct reports, Murphy, stops you to talk about a problem he’s having. You don’t have time to resolve it right then, so you say, “Let me think about it and get back to you.”

Guess what just happened?

Before that conversation, the monkey was on Murphy’s back. Afterward—it’s on yours.

Who owns the monkey? The person with the next step.

Murphy just delegated up. And you accepted.

That’s how managers, often with the best of intentions, end up buried in work that doesn’t belong to them.

Why We Pick Up Monkeys

It’s usually not about ego—it’s about good intentions gone sideways:

- You think you can do it faster (and maybe better).

- You want to be helpful.

- You feel guilty because your team is already swamped.

But here’s the problem: doing the work for your people doesn’t help them grow. And it doesn’t help you stay focused.

The Shoe-Tying Test

Picture this: You’re trying to get out the door. Your daughter, Courtney, is struggling to tie her shoes. You could stop and coach her… or just do it for her so you can get moving.

But if you always tie her shoes, she’ll never learn.

Leadership is no different. The best managers build strength in their teams—even when it takes longer in the short term. That’s how you grow performance, trust, and accountability.

It’s also how you protect your own time.

The more capable your team is at handling their own monkeys, the more you can focus on yours.

So How Do You Say No Without Being a Jerk?

It’s not easy. But it is possible—if you learn the art of the “positive no.”

William Ury coined the term in his book The Power of a Positive No. It’s a simple framework to say no constructively and clearly:

- Start with a “Yes.”

Affirm the relationship and your willingness to help. - Say “No.”

Establish your boundary. - End with a proposal.

Offer a next step—on your terms.

Example 1: Make an Appointment

Let’s say Murphy corners you in the hallway.

“Murphy, I’m happy to talk about it—but I don’t have time right now. Let’s set up a time to discuss it.”

Just like that, you’re helpful and in control of your time. And sometimes, Murphy will even say, “Never mind—I can handle it.” Monkey avoided.

Example 2: Defer the Yes

If you’re overloaded but still want to support your team, try this:

“I’m glad to help—but I’m maxed out today. Can it wait until Thursday afternoon?”

That’s supportive, but it keeps your priorities intact.

Example 3: Require Initiative

If Murphy does need your help, make it clear: he has to come with a proposed solution. Otherwise, his monkey will leap onto your back again.

Before the meeting, ask him to bring at least one idea. That way, he owns the problem—and you can coach, not solve.

Leadership Is About Empowerment, Not Heroics

You’ll always get more requests than you have time to fulfill. The key is to stay in control without shutting people down.

The “positive no” helps you:

- Protect your schedule

- Empower your team

- Reduce stress

- Build stronger performers

It works. When I started using it, I was surprised how well people responded. They were more understanding than I expected. And for the first time, I had breathing room to focus on the work that was actually mine.

So, the next time you’re walking down the hall and Murphy tries to hand you a monkey, remember:

Say yes to the relationship, no to the work—and yes again to a plan.

That’s how you stop being a monkey magnet.